Father of sake brewing in America

It’s surprising, ten years after it shut its doors forever, how many people remember the Honolulu Sake Brewery. That broad expanse of corrugated grey roofing at the foot of Pacific Heights was a familiar landmark for those driving along the Likelike Highway as it rose towards Nuuanu Pali. The building had stood there since 1908, the oldest sake brewery outside Japan and the first successful local Japanese-owned business in Hawaii. In its early years the Honolulu Sake Brewery was stop number two, after the Consulate General of Japan, for any business VIP or government official visiting the Islands from Japan.

I knew nothing of this background the day I first drove up to the brewery over twenty years ago. Misako Uemura, a staff writer for the Hawaii Times, had invited me to meet Takao Nihei, who had taken over management of brewery operations in 1956. Although I had never met Nihei-san, I was already a big fan of his sake, Takara Masamune. Thrifty Drugs in Kaimuki usually had it on the shelf, and I quickly discovered that icing the bottle down in the freezer before opening made it crisper, cleaner and a terrific pau hana companion for poki or boiled peanuts. Whenever Long’s ran a special on the big gallon-size, you’d see the issei retirees laying in supplies. Sure, it was cheap, but that wasn’t the only reason they drank it. It was also part of the history and culture of Hawaii.

Misako and I pulled into the brewery’s parking lot, and she pointed to the top of a weathered exterior staircase. “Nihei-san’s office is up there,” she said. “Let’s go on up.” It was a small room and looked like something out of the Taisho Era, a comforting mix of old and new, Japanese and Western. The bookshelves groaned under thirty years’ accumulation of the Journal of the Brewery Association of Japan. The furniture looked like it has been there since 1910, and a Shinto shrine resided in the room’s southwest corner. Meanwhile, jars, beakers and bottles of various shapes and sizes crowded the brewery manager’s desk and other available surfaces. “Make yourselves at home,” a voice called out from the adjacent room which Nihei-san used as a laboratory. “Here’s my home-made nigorizake with a little moromi mixed in from the vats–let’s give it a try!”

And then, there he was. Average height and build. Lively, intelligent eyes behind a pair of glasses that rarely let his face. White shirt and tie beneath his uniform jacket. Nothing remarkable in any way about his physical appearance. It was only when he began to talk, and then, as the sake began to flow, launch into an endless succession of anecdotes, observations, jokes, technical asides, gossip and reminiscences that it struck me that the brewmaster of the Honolulu Sake Brewery was one of the most charismatic people I’d ever met. His passion for brewing seemed to have become his passion for life. Or maybe it was the other way around. In any event, I’d never met anyone who could pack so much energy, intelligence and enjoyment into two hours of sake-drinking.

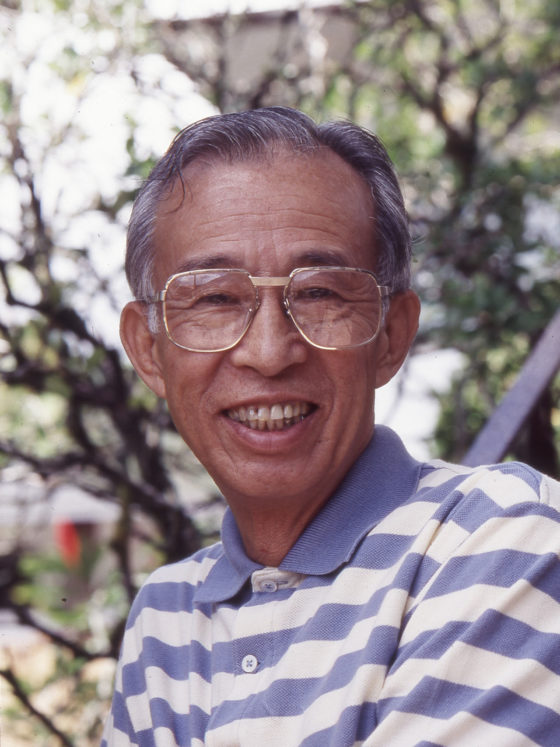

Takao Nihei

Takao Nihei was born in 1925 in Tokyo, but both of his parents were from Tohoku, then one of the most impoverished parts of Japan. He attended Tohoku Aeronautical Engineering Academy during the war, and then worked briefly in Morioka for a company that manufactured agricultural machinery. His break came in 1947 when he received an invitation to join the National Frementology Research Institute, a government agency attached to the Ministry of Taxation. There, studying under such famous technicians as Shiichi Yamada and Yasuyuki Kobuyama, he threw himself into scientific research as well as the culture and traditions of Japan’s brewing world.

These were the days before Japan’s rapid modernization, when traditional ways were still widely practiced. With his teacher Kobuyama-sensei, the young research chemist set out to visit progressive regional breweries eager to learn the new techniques being advanced by Tokyo. The ones they helped would later become the great houses of the sake world: Masumi, Uragasumi, Dewazakura, Koshi no Kanbai, Akitabare: these and many others benefitted from the scientific expertise of the travelling research technicians. But it was a two-way exchange as well. Some important technical innovations were being made by the breweries themselves; in 1946 Senji Kubota of Miyasaka Sake Brewing Company had discovered a new form of yeast that was so easy to use and had such a lovely aroma that breweries all over Japan were able to aspire to the production of ginjo sakes. From this combination of laboratory work and field studies, Nihei-san developed a reputation as the best and brightest of his generation, a man whose future in the sake world was assured. His classmate Hideo Abe recalls that he was also the best sake brewer at the research institute at that time–a hands-on sake virtuoso equally at home in the laboratory or the brewery floor.

In 1954, when Nihei-san was 28 years old, the Research Institute received a request from the Honolulu Sake Brewery to dispatch a research technician to Hawaii. Sake brewing had been prohibited during World War II, and attempts to revive it had met with failure. Brewing sake is difficult even in the best of circumstances, and with the pre-war brewery workers now retired, equipment in disrepair and its proud history in tatters, the brewery owners turned to Japan for help. They requested that a research technician be sent so that production could resume and the thirsty, long-suffering residents of Hawaii get some relief.

The rest of the story is well-known, how Nihei-san travelled to Honolulu in 1954, leaving his new bride Misako behind in Tokyo, and rescued the Honolulu Sake Brewery from almost certain oblivion. How he returned to Japan, but was recalled in 1956 when once again the difficulties of brewing sake in a tropical climate proved too much for the brewery staff. This time he brought Misako with him and settled in Hawaii; his daughter Yoko, the first of three, was born in 1956. When I asked him one time why he had decided to stay in Hawaii when he could have gone straight to the top in Japan, he told me it was because of the issei he had met. Nihei-san was a feisty man but he mellowed considerably after the third glass, and this is what he said: “They worked so hard in those sugar cane fields, and they had barely enough money for food and clothes, let alone a glass of sake. But when the Honolulu Sake Brewery started up, all over Hawaii people could afford at least a glass on Saturday night. Many people told me that if it hadn’t been for that one glass of sake, for that brief respite from the cares of the day, for that renewed glimpse of the forgotten dream that had drawn them to Hawaii in the first place, they would have given up and headed back to Japan. And that’s why I decided to stay in Hawaii and make sake.”

The Honolulu Sake Brewery ceased operations in 1989, and Nihei-san passed away in 1994. A couple years later the old brewery building on Pacific Heights was razed to the ground so that its new owners could put up a townhouse development. For those of us who sadly watched during these years it seemed like the final end of an era. But then, gradually, we began to realize that Nihei-san’s legacy lived on, through the activities of the Kokusai Sake Kai (International Sake Association), which organizes the U.S. National Sake Appraisal in Hawaii every year; through the loyalty of those old fellows who still line up at Long’s even though Takara Masamune is made in L.A. now instead of Honolulu; and through the enthusiastic attention and respect that the many people he taught about sake give to that inviting glass in their hand. More than just living on, it seems to be growing stronger year by year, as though the energy, dedication and aloha he put into his life’s work is reaching its final fruition today.

***

This articles was written by Chris Pearce, president of World Sake Imports, and was originally published in the Hawaii Herald.